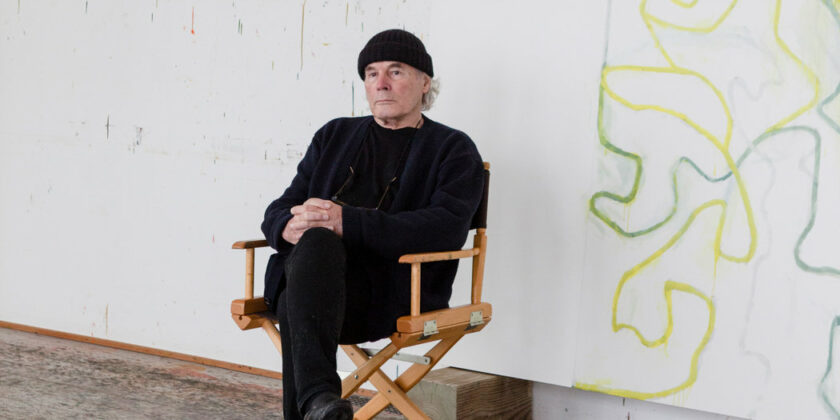

Brice Marden, whose elegant fusion of minimalism and Abstract Expressionism in the 1960s revivified painting and established him as one of the most admired and influential artists of his generation, died on Thursday at his home in Tivoli, N.Y., in Dutchess County. He was 84.

The cause was cancer, his wife, Helen Marden, said in a statement.

In the mid-1960s, when conceptual art, Pop Art and minimalist sculpture were in the ascendancy and painting was declared dead by many critics and artists, Mr. Marden issued a powerful counterstatement.

His paintings, first exhibited in New York at the Bykert Gallery in 1966, seemed irreducibly minimalist at first glance — a solid field of color for each canvas, in ambiguous gray and green tones, with an unpainted one-inch strip at the bottom where drips of paint ran over. On closer inspection, the matte surfaces, achieved through a mixture of oil paint and liquefied beeswax, opened up to reveal intricate textural layerings, applied with brush and spatula, that reflected his preoccupation with masters like Zurbarán, Goya and Cézanne and his total rejection of the impersonal aesthetic of conceptualism and minimalism.

“It seems as though, because the early paintings were just one color, one could say one color, no feelings — but instead of no feelings they were all this feeling,” Mr. Marden told Bomb magazine in 1988. “Each layer was a color, was a feeling, a feeling that related to the feeling, the color, the layer beneath it. A concentration of feelings in layers.”

The critical response was overwhelming, propelling Mr. Marden to art-world stardom while still in his 20s. Hilton Kramer, reviewing the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s retrospective of his work in The New York Times in 1975, called Mr. Marden not simply a painter but the leader of an entire school.

“The art journals follow his work with close attention,” he wrote. “Younger painters, scarcely out of school, take his work as a model the way their counterparts once took Willem de Kooning’s and Jasper Johns’s and Frank Stella’s.”

Mr. Marden maintained this exalted status throughout his career. In his five “Grove Group” paintings of the early to middle 1970s, inspired by the olive trees he saw on his annual visits to the Greek island of Hydra, he introduced modulated greens, browns and blacks into his canvases; in the vibrant “Summer Table” (1972-73), he introduced pulsing blues and a searing yellow. “After a summer in Greece I felt the light should be intenser, clearer and less shrouded,” he wrote in 1973.

In the 1980s, Mr. Marden took a dramatic new turn. After seeing an exhibition of Japanese calligraphy, and visiting Asia for the first time, he developed a style based on Chinese calligraphy, weaving loops and ropes of color into webs of overlapping and intersecting lines that covered large-scale canvases. Initially angular, they evolved into sinuously elegant ribbons of color.

The “Cold Mountain” series, produced between 1989 and 1991 and based on the Zen poems of the Chinese writer Han Shan, epitomized his new approach, which seemed to wed Asian influences with the linear work of artists like Piet Mondrian and Jackson Pollock.

Where Mr. Marden led, his audience followed, as did critical acclaim. In 2006 he was the subject of a career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art that gave an official stamp to his standing as a major artist. He was, The Wall Street Journal wrote, “among the handful of living artists established enough to be considered part of art history.” Peter Schjeldahl of The New Yorker called him “the most profound abstract painter of the past four decades.”

Nicholas Brice Marden Jr. was born on Oct. 15, 1938, in Bronxville, N.Y., and grew up in nearby Briarcliff Manor. His father worked for a mortgage servicing company. His mother, Kathryn (Fox) Marden, was a homemaker.

As a teenager, he made the pages of The New York Times when he sold $5 shares in himself to finance a trip to Texas, pledging to return principal and interest to his investors. He came back rich in experience but with only $10 in his pocket.

A lackluster student, he enrolled in Florida Southern College with an interest in art that had been encouraged by a kindly neighbor who bought him a subscription to Art News. After a year he transferred to Boston University, where he painted self-portraits and still lifes and, in 1961, earned a B.F.A. degree from the School of Fine and Applied Arts.

While in Boston, he became immersed in the city’s folk music scene and married Pauline Baez, the older sister of the singer Joan Baez. The marriage ended in divorce. In addition to Helen Marden, his second wife, he is survived by a son from his first marriage, Nicholas; two daughters from his second marriage, Mirabelle and Melia Marden; a younger sister, Mary Carroll Marden; and two grandchildren. His brother, Michael, died in 2010.

While attending Yale University’s summer school in Norfolk, Conn., Mr. Marden ventured into abstract painting, He continued to follow that path at the Yale University School of Art, where his classmates included the painters Nancy Graves and Chuck Close and the sculptor Richard Serra. It was at Yale that he began working with a muted palette and pledged allegiance to the rectangle, at a time when many painters, notably Frank Stella, were starting to use shaped canvases.

“I had this whole idea, especially with the monochromatic paintings, of you could get the exact perfect right color for that shape, and if you did, if you really got it right — say, if you had absolute correctness of form — God knows what the painting was capable of doing,” he told Harry Cooper, a curator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, during a studio visit in 2009. At the same time, many of his titles, referring to people, places or events, invoked a world beyond the painting’s frame.

After receiving a master’s degree in fine arts in 1963, Mr. Marden moved to New York. He found a part-time job at Chiron Press, a silk-screen printing shop, where he worked on the first “Love” poster by Robert Indiana. He was hired as a guard at the Jewish Museum, where a Jasper Johns show greatly influenced his ideas about touch, surface and abstraction. He later worked as a studio assistant for Robert Rauschenberg.

His first monochromatic panels were exhibited in 1964 at Swarthmore College and, soon after that, at the Bykert Gallery. “People were saying, painting was dead. And this was my way of thinking, well, there are things that haven’t been done,” he told Mr. Cooper of the National Gallery.

In 1968 he began joining his panels in twos and then threes, as in the final painting of the “Grove Group” and in the “Red, Yellow, Blue” series” of 1974. The monochromatic painting reached a kind of apotheosis in the “Annunciation” series of 1978, five three-panel works in primary colors alluding to the five states of mind experienced by the Virgin Mary after she was told by the Archangel Gabriel that she was to bear the son of God. John Russell of The New York Times called the series “one of the richest, clearest and most fulfilled of our century’s grand designs.”

In the early 1980s, as neo-Expressionists like Julian Schnabel brought turbulence and drama to painting, Mr. Marden began searching for a new idiom. “I came to feel that my work had reached a point where it was too preoccupied with refining a concept,” he told Art in America in 1987. In an interview with Flash Art magazine in 1990, he said that he faced “silent creative death.”

A long trip to Sri Lanka and India kindled an interest in the arts of Asia, reinforced by an exhibition at Japan House and the Asia Society in New York, “Masters of Japanese Calligraphy.” He embarked on a series of paintings and drawings using a long-handled brush or long twigs to create gestural, calligraphic works that became the signature of his later career. The structure of Chinese calligraphy, he told Mr. Cooper, was “basically like a grid, so it wasn’t that far removed from what I was already doing.”

The scaffoldlike forms of paintings like “Diptych” (1986) and “Untitled No. 3” (1986-87), with their echoes of Cézanne and Cubism, loosened into the looping rhythms of the “Cold Mountain” series, his largest-scale works to date, with their orchestrated tangle of lines in black and brown, or assertive primary colors, against pale backgrounds.

In the “Red Rock” series, executed between 2000 and 2002, Mr. Marden employed vibrant colors, as he did with his “Grove Group” series; he also simplified his lines, with stunning effect. Doubling down, he took the same approach to a series of six-panel works, on an even grander scale, called “The Propitious Garden of Plane Image.”

In addition to his home in Tivoli, Mr. Marden maintained homes and studios in Manhattan; Eagles Mere, Pa.; and Hydra. In 2017 he learned that he had cancer, a diagnosis that did nothing to stem his output or his packed exhibition schedule. The next fall, the five-panel “Moss Sutra With the Seasons,” five years in the making, was installed in its own chapel at the Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Md. It was the largest commission of his career.

“I paint because it’s my work,” Mr. Marden told the documentarian Edgar B. Howard in 1976. “And I paint because I believe it’s the best way that I can pass my time as a human being. I paint for myself. I paint for my wife. And I paint for anybody that’s willing to look at it.”

Maia Coleman contributed reporting.

Source: Read Full Article